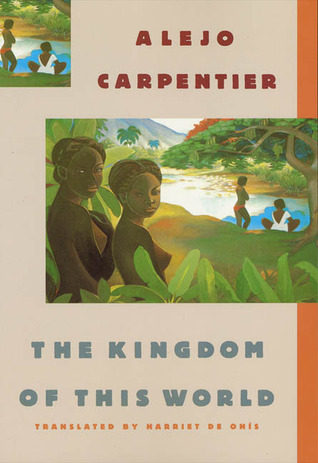

A few years after its liberation from French colonialist rule, Haiti experienced a period of unsurpassed brutality, horror, and superstition under the reign of the black King Henri-Christophe. Through the eyes of the ancient slave Ti-Noel, The Kingdom of This World records the destruction of the black regime--built on the same corruption and contempt for human life that brought down the French--in an orgy of voodoo, race hatred, erotomania, and fantastic grandeurs of false elegance.

Goodreads description

This is arguably the book that launched Latin American magic realism. First published in 1949, the book opens with a prologue which sets out to distinguish what the Cuban author calls the "marvellous reality" of Latin America from the surrealist marvellous of Europe: But what many forget, in disguising themselves as cheap magicians, is that the marvellous becomes unequivocally marvellous when it arises from an unexpected alteration of reality ( a miracle), a privileged revelation of reality, an unaccustomed or singularly favourable illumination of the previously unremarked riches of reality, an amplification of the measures and categories of reality, perceived with peculiar intensity due to the exaltation of the spirit which elevates it to a kind of "limit state".

You can read the full Prologue here

Carpentier succeeds in this book in delivering beautiful and powerful magic realism. One of the key points made in the Prologue is that the magical depends on who believes it. Ti-Noel, who stands at the book's centre, is a black slave who believes in voodoo and its powerful magic. It is suggested that when Henri-Christophe stops believing in voodoo and adopts Christianity he starts to lose his power. It is not an accident that his personal crisis takes place in a church. Voodoo drum beats herald revolutions and echo through the book. Macandal, the first revolutionary leader, is said to be able to turn into animals, as at the end in a turning of the circle does Ti-Noel. But neither are successful in their bids for freedom.

The story is ultimately a sad one. Ti-Noel and the black slaves throw off the brutal chains of one master only to lose their freedom to another - first their French slave owners, then black King Henri-Christophe who has them building a fantastic fortress palace in the jungle and neglecting their crops and finally the mulattoes with their measuring poles seizing the land. It is not a surprise that many have compared it to Animal Farm. As we know, the bloody history of Haiti has continued ever since. And yet there is something affirming about the book's ending: at the end Ti-Noel understands that a man never knows for whom he suffers and hopes. He suffers and hopes and toils for people he will never know, and who, in turn, will suffer and hope and toil for others who will not be happy either, for man always seeks a happiness far beyond that which is meted out to him. But man's greatness consists in the very fact of wanting to be better than he is.

Carpentier uses nature symbolically throughout the book. There is Macandal and Ti-Noel's shape-changing. Henri-Christophe's fortress is being covered by lush red fungi even as it is built. When Ti-Noel returns to the plantation where he had been a slave, he finds it destroyed and overgrown. Nature is at once on the side of the slaves (they are aided by the weather and poisonous plants) and yet at the same time it is beyond them.

Regular readers of this blog will know how I believe in the value of magic realism in accurately portraying history, for the very reason Carpentier sets out in the prologue - what is magic depends what people believe. Anyone wishing to get a feel for the history of Haiti would do well to read this book, which reveals as much about the island and its past as any non-fiction account.

This short book (150 pages) is unquestionably one of the masterworks of magic realism. Read it.

No comments:

Post a Comment