He could outrun anybody, and he never missed a day of school. He saved lives, tamed giants. Animals loved him. People loved him. Women loved him (and he loved them back). And he knew more jokes than any man alive.

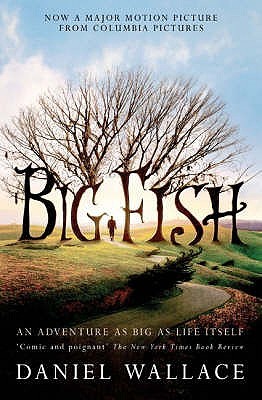

Now, as he lies dying, Edward Bloom can't seem to stop telling jokes -or the tall tales that have made him, in his son's eyes, an extraordinary man. Big Fish is the story of this man's life, told as a series of legends and myths inspired by the few facts his son, William, knows. Through these tales -hilarious and wrenching, tender and outrageous- William begins to understand his elusive father's great feats, and his great failings.

Goodreads description

What a fascinating book! I found myself thinking about it for days after I had finished reading it and have delayed writing this review as a result. Big Fish works on all sorts of levels. It is deceptively simple: the story of a young man facing his father's impending death and realizing that he does not really know him from the personal mythology that his father has woven about himself. The book regularly references classical myths: for example Hercules' labours and Ovid's fish metamorphosis . Edward is in some ways trying to make himself larger than life, even immortal with his tales.

William wants to understand whether his father believes in heaven and immortality. When he asks, Edward replies with a joke in which Jesus meets an old carpenter at the Pearly Gates, who tells him that the only remarkable thing about him is his son: "He went through a most unusual birth and later a great transformation. He also became quite well known throughout the world and is still loved by many today." Jesus hugs the man saying "Father, Father!" to which the old man replies "Pinocchio?" This joke is a wonderful example of Wallace's layering of images and symbols. There is clearly a parallel drawn between the three father/son relationships and the son mistaking the father. But it is also a double sleight of hand: the joke is Edward's way of hiding from his son, but it also reveals how he does it - by distracting the hearer from the truth: the old man is not god, just as Edward is not.

It is these layers that mean that this is not some sort of Walter Mitty or Baron Munchhausen story. The book is about reality and a terrible reality at that. It is about what makes a man and what makes him great. Throughout his life Edward is trying to be a "big fish", a great man. To do that he leaves behind his home and his family and roams the world, seeking acclaim and fortune, the American Dream. As he is dying he dreams that his garden fills with people who admire him, trampling on the flowers and overwhelming his wife and son. But at the end he needs his son to affirm his greatness. William's response is that a great man is one loved by his son.

I could spend hours discussing the many images and stories in this novel and still not do them justice. I was reading on a forum discussion recently that "magic realism is like living in a poem" and this book certainly falls within that definition and just as poetry has perhaps a more profound reality than many a piece of realistic fiction, so the same is true of Big Fish. The book ends with a final flourish of magic realism, which is unexpected. But then earlier William had said that the ending is always a surprise. I should have known to expect the unexpected.

No comments:

Post a Comment